“Until he finally reached retirement age, Willoughby was a problem,” penned Louis B. Wright in Of Books and Men (University of South Carolina Press, 1976, p.135), looking back on two decades as Folger Director, 1948–1968.

I had not thought about Edwin Willoughby for years. Then, on September 20, 2021, I visited Mary L. Martin Ltd, the world’s largest postcard shop, located near the Susquehanna River in Havre de Grace, MD. Expecting me, Mary had laid out on a counter four boxes of postcards each marked LIBRARY. Since the cards were sorted alphabetically; I quickly found 7 postcards of the Folger with messages and postmarks, quite a haul for a modest $5. Only when I got home did I discover that one sent in 1952 was signed . . . Edwin E. Willoughby.

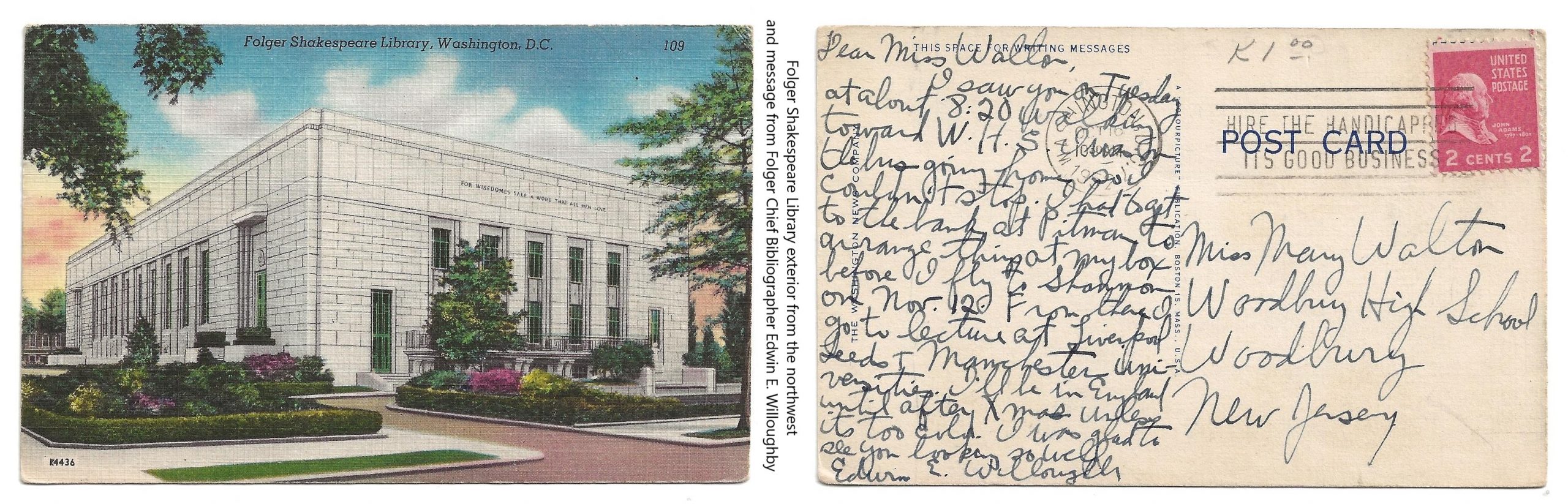

Fig. 1. Folger Shakespeare Library exterior from the northwest and message from Folger Chief Bibliographer Edwin E. Willoughby

On Oct. 16, 1952, Edwin Willoughby wrote to Miss Mary Walton, Woodbury High School, Woodbury, New Jersey:

Dear Miss Walton,

I saw you on Tuesday at about 8:20 walking toward W.H.S. I was on the bus going home so couldn’t stop. I had to get to the bank at Pitman to arrange things at my box before I fly to Shannon on Nov. 12. From there I go to lecture at Liverpool Leeds & Manchester Universities. I’ll be in England until after Xmas unless it’s too cold. I was glad to see you looking so well.

Edwin E. Willoughby

Representing the Folger, Willoughby was about to travel to England to lecture at three British Universities. He retired in 1958 after 23 years at the Folger as Chief Bibliographer.

While tempted to speculate on Willoughby’s message, instead I got out the notes of an interview I conducted with a Folger staffer, Jean Miller, in the periodical room on Deck B on Feb. 11, 2011. My notes read: “Louis B. Wright hired Jean in 1952. She knew Edwin E. Willoughby, Chief Bibliographer. Jean called him ‘a character!’ When she first met him at tea, he said, ‘I have to organize the Army of God!’ He had a girlfriend named Fulbright, related to the Senator somehow.”

My curiosity piqued, I contacted Jim Gerencser, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA., where the Willoughby Papers are located. “She [Miss Mary Walton] was likely one of Edwin’s teachers. He appears to have graduated from Woodbury in 1918,” Jim wrote.

I figure out that Miss Mary Walton was 65 years old when Edwin spotted her on the street. Mary was born in Woodbury, N.J. in 1887. She graduated from Woodbury High School in 1905, and Mt. Holyoke College in 1912. She moved back to Woodbury where she taught at the High School for 39 years.

Edwin was engaged once, but never married. He died at 60, survived by his mother.

Both Edwin E. and Louis. B were born in 1899. They each received Guggenheim Fellowships for the Humanities in 1929. Wright’s work at the British Museum resulted in Middle Class Culture in Elizabethan England (University of North Carolina Press, 1935). Willoughby’s work was also at the British Museum at the same time and led to the publication of Printing of the First Folio of Shakespeare (Oxford University Press, 1932). The two scholars must have rubbed up against each other frequently.

1929 was a critical year for other reasons. Henry Clay Folger retired from Standard Oil Company after 49 years. The stock market crashed, cutting in half the value of the fortune Folger had amassed from his oil stock holdings. The 14 brownstones on East Capitol St. SE were razed to make way for the construction of the Folger Library. The year 1929 was Henry Folger’s last full year of collecting before he died.

In Wright’s book, The Folger Library: Two Decades of Growth – An Informal Account (University Press of Virginia, 1968), the author was pleased to note that the BBC praised the “brilliant use of technical evidence” Willoughby presented in The Printing of the First Folio.

In Of Books and Men, Louis B. has more to say about his fellow researcher (p.134-135)—and none of it flattering:

The Folger catalogue, such as it was in 1948 was also a curious anomaly, the creation of Edwin Willoughby, an eccentric who had been made head of the catalogue department sometime before. He invented a system of classification based on the name “William Shakespeare.” Fortunately few reference works had been bought and thus classified. We quickly adopted the Library of Congress classification system and tried to forget “William Shakespeare” as a key to locating books. More serious was a scheme to catalogue or further describe the rare books in infinite detail. The result had been an attempt at an elaborate bibliographical description on cards, even to hand-drawn pictures of watermarks in the paper and any other bibliographical curiosity. I calculated that it would take more than two hundred years to complete his task, even if we never bought another rare book. Even worse was the discovery that many bibliographical descriptions were inaccurate.

We had no recourse but to find another slot in the library for Willoughby and to make Paul Dunkin chief of the catalogue department. . . . If he [Willoughby] did a stint at the reading-room desk, he would usually fall asleep. Working in the stacks on some bibliographical problem, he liked to sing––in ghostly tones that sometimes frightened new staff members unfamiliar with this phenomenon. . .

Fig. 2. Edwin E. Willoughby. Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA

Fig. 3. Folger Director Louis B. Wright. Folger Shakespeare Library.

In comparison with Louis’ unflattering portrayal of Willoughby and his quirks, my own depiction of the man in Collecting Shakespeare pales in liveliness but offers some complementary information (p.189-190):

Edwin ‘Eddie’ Willoughby also applied for a reader’s card the first year. An eccentric and controversial fellow, Willoughby lived in a room at the Dodge Hotel near Union Station. He had earned his doctorate in Library Science at the University of Chicago. After a two-year fellowship at the British Museum, he authored a book on the printing and publishing of Shakespeare’s First Folio. Recognizing Willoughby’s scholarship, Adams hired him as chief bibliographer, and in 1935 put him in charge of producing the library’s first catalog of the book collection. Willoughby started with the Short-Title Catalogue of Books Printed in England, Scotland, and Ireland from 1475 to 1640 (STC). Considering the Library of Congress classification system unsuitable for some of the Folger’s specialized holdings—with the unwieldy length of call numbers they would require—he devised a modified Dewey Decimal system of classification. Once the library adopted this system, it marketed it at a modest cost to other institutions, such as the University of Pennsylvania. During the directorship of Louis B. Wright in the late 1940s, however, the library shed Willoughby’s classification system and adopted that of the Library of Congress. Willoughby continued his own scholarly work and, with over a dozen books and many articles in American and British journals, added considerably to the Folger name.

Fig. 4. Folger Reference Librarian Giles Dawson. Library of Congress

It’s useful to read what a Folger colleague thought of Willoughby. Here is Reference Librarian Giles Dawson’s take on the man: “Willoughby was one of the most interesting, fascinating, men I‘ve ever known. . . I often ate lunch with Willoughby, and not infrequently had him for dinner at home, though my wife was not very fond of him. . . he was a thoroughly mixed-up man.” (Dawson, Giles. “History of the Folger Shakespeare Library, 1932–1968.” Unpublished manuscript, 1994. p.20, 22, 31. Folger Shakespeare Library)

Did Willoughby have other supporters? He did. On Jan. 30, 2014, Frank Mowery, former head of the Folger’s conservation department, replied to a post here on The Collation saying “My Dad was a librarian . . . [and] a big fan of Willoughby.”

Figs. 5a. & 5b. Of Books and Men by Louis B. Wright

Book cover, inscribed title page by son Chris Wright

On an impulse, I queried Louis Wright’s son Christopher on September 30, 2021 about Willoughby. His emailed comment fits right in: “I do remember Willoughby because his name was curious to a small boy and I faintly recall some dinner table conversation between my parents about him that I wasn’t to repeat!”

Readers, what do you say about Willoughby for the Folger character award?

Finding a Folger postcard written and signed by Willoughby was a thrill; the Willoughby Papers at Dickinson do not include any postcards Willoughby sent. It got me to thinking: What are the chances I might find a Folger postcard written by a Folger director? One written by O. B. Hardison Jr., Louis B. Wright, Joseph Quincy Adams, or William Adams Slade? Or by the three Folger directors captured on Oct. 3, 2019 in the Great Hall? I’ll keep looking.

Fig. 6. Folger Shakespeare Library Directors

Werner Gundersheimer, Michael Witmore, and Gail Kern Paster

At the Folger on Oct. 3, 2019. Photo by Stephen Grant

Stay connected

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Comments

Thanks for this trip down memory lane, Stephen! I remember the quirky Willoughby system that arranged the books in the H.H. Furness Reading Room at Penn during my graduate days. As I recall, it was based on an idiosyncratic scheme with titles grouped and numbered from 1 to 98, some with a Cutter or two. I later assisted Dan Traister in culling and de-duping Furness modern copies catalogued under the Willoughby system book-by-book as a part-time special collections staffer.

Owen Williams — February 17, 2022

Steve Grant, with his usual archival resourcefulness and interest in all things Folger, has given us a wonderful portrait of Eddie Willoughby and a glimpse into the early history of Folger cataloguing. I love his description of Willoughby’s quirky classification system and Louis Wright’s utter frustration with it. I sympathize from the bottom of my directorial soul, and also applaud Wright’s decision to rusticate Willoughby and wait for his retirement.

Gail Kern Paster — February 23, 2022

Steve Grant, the Folger’s eminent deltiologist, has followed the postcard highway into an unusual and colorful trail through the Washington cultural swamp. Among the unique and idiosyncratic fauna lurking in the shadows of the Folger’s early days, he has (re) discovered bibliographer E. Willoughby, and presented new insights into the habits and behavior of this now-extinct creature, a gentle albeit peculiar example of the book person’s breed. Grant gives us all proof positive, if any were needed, that one thing can lead to another.

Werner Gundersheimer — February 23, 2022